Anyone considering the purchase of an all-electric vehicle is faced with a number of questions, but one in particular is unfortunately much harder to answer than it should be – the comparative cost of running an electric versus a gas vehicle.

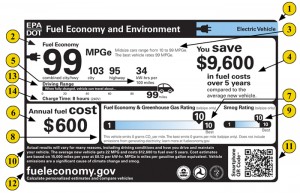

People are used to thinking in miles per gallon, but that no longer works. It is one of the reasons that the EPA has introduced new mileage stickers for all vehicles – gas, hybrid and electric. But a welter of numbers and new terms that are meant to help comparability – MPGe, kWh/100 miles, eGallon – seem only to add to the confusion.

Let’s get one misconception out of the way first, though – the idea that it doesn’t make sense to buy an electric car unless it “pays for itself” through the lower cost of fuel. We don’t apply that requirement to most of the decisions we make when buying a car. We may make many choices that add cost when we buy a vehicle – manufacturer (Lexus or Toyota), configuration and size (SUV, cross-over or minivan), model (300 or 500 class, XLE or GLE) and a myriad of optional features. But no one seriously expects to make up those differences through operational savings. You have many reasons for buying a specific vehicle. So you can certainly choose to buy an electric car without calculating how much you will save in fuel costs.

That said, it will cost less to run an electric car than a similar gas-powered car, so it is reasonable to want to estimate those savings and account for them when making the purchase decision. How can we calculate, or at least estimate, the difference?

Here’s a ballpark estimate – $1,000 per year. There are a lot of assumptions and averages built into that estimate. That’s why “your mileage may vary” has entered the language as a all-purpose way to say “it depends”, so let’s take a deeper look.

The key variables for all vehicles are the cost of the fuel, how far the car can go per unit of fuel and how many miles you drive. Let’s start with a gas-powered car that gets 25 mpg, assume that gas is $3.49 per gallon and that you drive 12,000 miles per year:

The calculation for an electric car is similar, but you need different numbers. Electricity is measured in kilowatt hours. In Massachusetts, electricity costs about $0.16 per kilowatt hour (kWh). The unfamiliar number is how far an electric car goes per “unit of fuel”, or miles/kWh. That information is on the new EPA mileage sticker, but it’s not the large MPGe number. It’s hidden in the smaller number next to MPGe, and listed as kWh per 100 miles. A typical number for the current generation of electric cars is 34 kWh per 100 miles. 34 kWh for 100 miles is the same as .34 kWH for 1 mile. Since the units are reversed (kWh/m instead of miles/kWh, this time we multiply the numbers:

The difference – $1,022 – is the estimated yearly savings from driving an electric vehicle with these assumptions.

With a bit of rearrangement and substitution, these calculations offer some additional insights:

- Changes in the price of gas have a bigger impact than changes in the price of electricity. A 1 cent increase in the cost of electricity – 6.25% – would add $41 to the yearly cost. A similar magnitude increase in gas prices – 22 cents – would add $106.

- The more miles driven per year, the greater the savings from an electric vehicle. You can use the difference in the intermediate figure – 8.52 cents per mile – to estimate the cost difference based on your own yearly mileage. The more of those miles that are local, the greater the savings.

- To get the same level of yearly savings without buying an electric vehicle, you’d need to buy a car that got 64 mpg.

- Gas would have to fall to $1.36 per gallon to completely wipe out the fuel savings of an electric vehicle.

What about that MPGe number?

MPGe (miles per gallon equivalent) was created to provide a direct, apples-to-apples comparison between gasoline-powered vehicles and vehicles powered by other fuels. It estimates the total energy used by different fuels to travel a given distance under given conditions. To maintain consistency with the old, familiar MPG, the EPA normalized the calculations to the energy in a gallon of gas (as measured in BTUs, British Thermal Units). A car with a gas engine that gets 25 MPGe uses four times as much energy as an electric car that gets 100 MPGe.

MPGe (miles per gallon equivalent) was created to provide a direct, apples-to-apples comparison between gasoline-powered vehicles and vehicles powered by other fuels. It estimates the total energy used by different fuels to travel a given distance under given conditions. To maintain consistency with the old, familiar MPG, the EPA normalized the calculations to the energy in a gallon of gas (as measured in BTUs, British Thermal Units). A car with a gas engine that gets 25 MPGe uses four times as much energy as an electric car that gets 100 MPGe.

Measured as energy used, MPGe is a valid and appropriate comparison. It just can’t be used to compare cost, as MPG could.

What about Greenhouse Gas (GHG) Emissions?

That’s another story altogether. The new mileage sticker does provide some information, but it doesn’t tell the whole story. The sticker provides a relative scale (1-10) for greenhouse gas rating, and a number for tailpipe emissions, measured in grams CO2/mile.

For an all-electric vehicle like the Nissan Leaf, the tailpipe emissions are obviously zero. A gas/electric vehicle like the Chevy Volt emits about 80 g/m. A hybrid Prius c emits about 180 g/m. Mid-size gas vehicles like the Honda Accord, the Nissan Altima, the Toyota RAV4 and even the Lexus ES350 emit about 350 g/m. A Ford F150 pickup truck emits 520 g/m. So far, so good.

But tailpipe emissions don’t tell the whole story. There are upstream emissions that have to be considered. Greenhouse gases are emitted in the production and distribution of gasoline. Those add roughly 25% to the figures above for gasoline vehicles. For an all-electric vehicle, there are GHG emissions associated with the production of the electricity it uses. That will differ significantly in different parts of the country, so there’s no way to include that on a mileage sticker. However, the EPA provides a handy calculator to estimate the GHG emissions associated with the production of electricity needed to power a plug-in hybrid or electric car where you live.

Continuing our Nissan Leaf example, running a Nissan Leaf in Massachusetts would generate 120 g/m of CO2. The US Average is 190 g/m, so an electric vehicle in Massachusetts produces fewer greenhouse gases than one in Tampa, FL (180 g/m) or Dayton, OH (230 g/m). But even in those parts of the country with “dirty” electricity, an all-electric vehicle will still account for much lower levels of CO2 emissions than an equivalent gas-powered car.

Adding upstream emissions to tailpipe emissions, here are total estimated CO2 emissions for a group of representative vehicles:

| Nissan Leaf | 120 g/m |

| Chevy Volt | 200 g/m |

| Toyota Prius c | 222 g/m |

| Honda Accord (4 cyl) | 378 g/m |

| Honda Accord (6 cyl) | 443 g/m |

| Nissan Altima (6 cyl) | 443 g/m |

| Toyota RAV4 | 443 g/m |

| Lexus ES350 | 462 g/m |

| Ford F150 | 652 g/m |

Want to find out more? All the information about emissions, and much more, is available at the Find & Compare Cars page of the Department of Energy’s Fuel Economy web site.

One final caveat. It should also be noted that the tailpipe emissions for gasoline-powered vehicles are calculated, not measured. In Europe, which has vehicle emissions standards in addition to mileage standards, vehicle emissions have to be measured. Europe’s current standard for emissions is 209 g/m[1], and the estimated European fleet average is currently 212 g/m. The estimated emissions of the average new vehicle sold in the US is 500 g/m, so we have quite a way to go.

Other Resources to learn more

The EPA’s new mileage labels

Notes:

- ↑ European standards are of course expressed in grams/kilometer, not grams/mile. I have made the conversion for comparability with US standards.